This is part 1 of a multipart series on triads:

- Triad introduction and close-voiced triads on G/B/E (this page)

- Triads on other strings using octave drops

- Harmonizing scales with triads

Chords are just any number of notes played simultaneously. Technically, you could have two-note chords (AKA dyads) but most people consider three-note chords (called “triads”) to be the simplest possible place to start making useful chords. The four triad types form the “atoms” of western harmony.

Any song can be reduced to combinations of simple triads. Even extended or altered chords with many more than just three notes can be thought of as a combination of two or more triads played simultaneously. If you played a G major triad at the same time someone else played a B diminished triad, for example, together you would make the sound of a G7 chord.

Triads are formed by “stacking” two intervals of a 3rd (major or minor) on top of each other. Since there are two intervals, and each interval can be either major or minor, there are logically four types of triads:

-

Major: root + M3 + p5 (a major 3rd between the first two notes, and a minor 3rd interval between the next two)

-

Minor: root + m3 + p5 (a minor 3rd between the first two notes, and a major 3rd between the next two)

-

Diminished: root + m3 + ♭5 (two minor third intervals stacked on top of each other)

-

Augmented: root + M3 + ♯5 (two major third intervals stacked on top of each other)

The first two (major and minor triads) are by far the most common and most useful for playing songs. You should definitely learn them first.

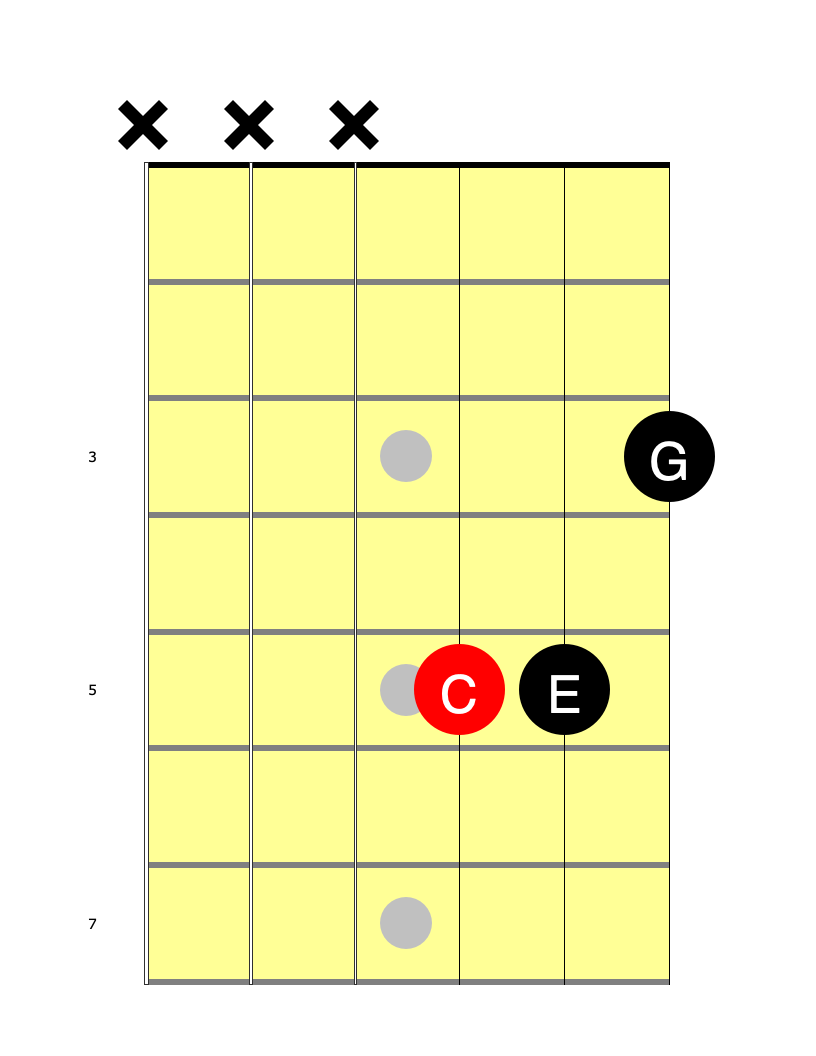

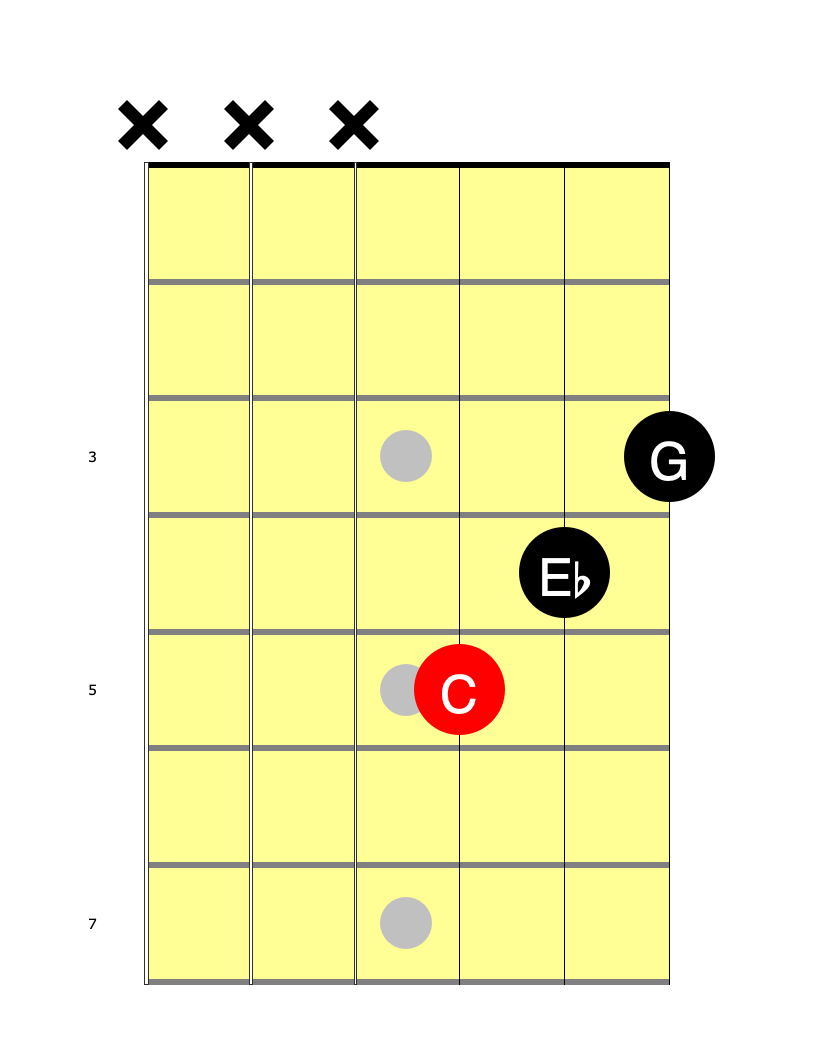

The C Major triad comprises the notes C, E, and G (skipping the intervening notes: C d E f G). It’s a minor 3rd stacked on top of a major 3rd. The M3 interval between C and E is what gives the chord its “happy” sound.

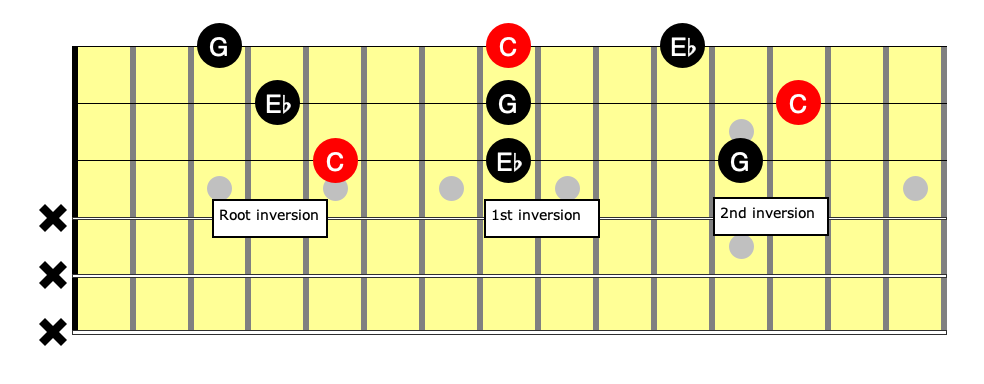

The C minor triad comprises the notes C, E♭, and G. This time the minor 3rd between the first two notes is what gives it the “sad” or “poignant” quality.

Here is how to play the C Major and C minor triads on the top three strings:

As you can see, simply moving the 3rd (the middle note) down a half step changes the quality of the chord from major to minor.

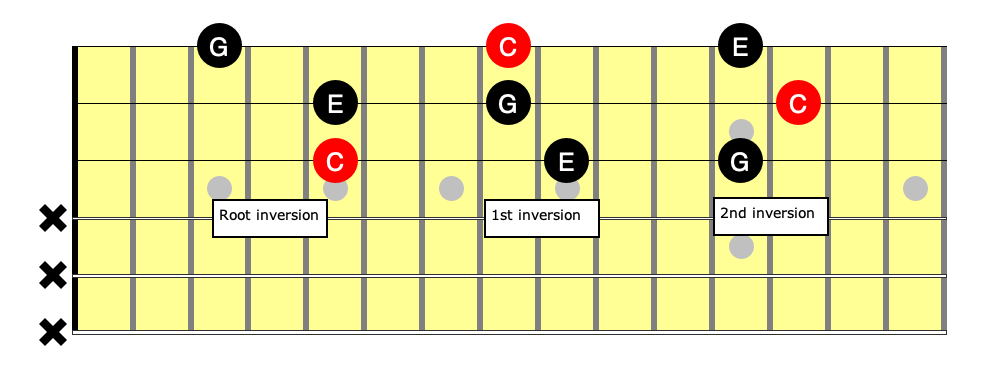

When the notes are in order like this (ordered root, 3rd, 5th from lowest pitch to highest) we call the form of the triad the “root position” or “root inversion”.

There are other orderings of the three notes besides the root inversion, of course. The six permutations of the three notes in the C Major triad are: CEG, EGC, GCE, CGE, ECG, and GEC.

The first three of these groupings are called “close voicings” because the notes are as close together as possible. The others are called “spread voicings” or “drop chord voicings” because one of the notes (voices) is moved to a different octave and is no longer as close as possible to the others.

ECG is a spread voicing, for example, because there is another G in between E and C that is skipped over (the G in the chord is in a higher octave than the E). The E that was previously between the C and G in root position was “dropped” an octave. On the fretboard, you can only play a spread voicing by skipping at least one string. Only close voicings are playable on three adjacent strings.

We will limit ourselves to close voicings for the remainder of these pages. Spread voicings are a more advanced topic that you should explore on your own.

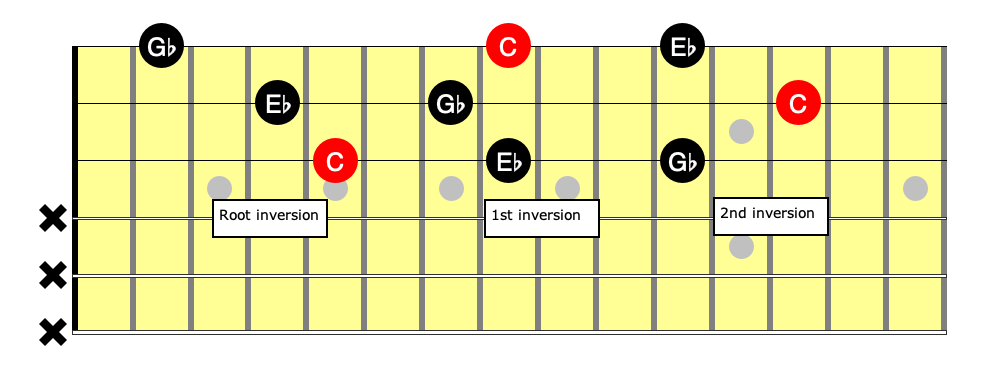

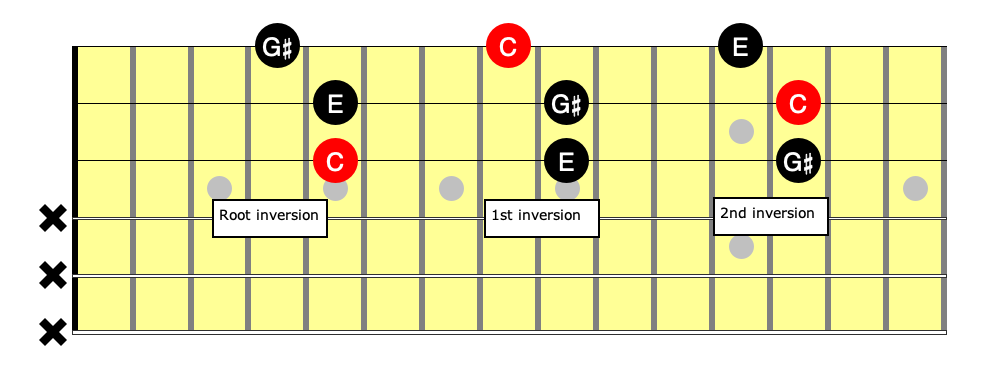

The three close voicings for C Major are:

-

CEG (root inversion, with the root in the bass)

-

EGC (1st inversion, with the 3rd in the bass)

-

GCE (2nd inversion, with the 5th in the bass)

On the top three strings of the fretboard, they look like this:

Notice that when moving up the neck to the next inversion, each “voice” in the triad (lowest, middle, or highest pitch) moves up to the next higher note. The C (root) on the 3rd string moves to E (M3), E moves to G (p5), and G moves to C (root). CEG → EGC. The same thing going from first to second inversion: EGC → GCE. And again when repeating the next higher root inversion (at frets 15-17 if you can reach): GCE → CEG.

These three shapes allow you to play any major chord! If you move any of these three shapes two frets higher, it forms D Major (the notes D, F♯, and A).

I recorded this video a while ago. Nothing in it that isn’t explained above, but in case it’s easier to follow on an actual guitar:

It’s very important to remember where the root note is in each of these shapes. While accompanying other musicians, you’ll often find yourself only thinking about the root notes of each new chord. You’ll then find the closest location for that note and form the rest of the shape around it.

If you want to play G major, for example, you can choose between the G at the 12th fret 3rd string, 8th fret of the B string, or 3rd fret of the E string. It’s then just a matter of forming the shape appropriate for the root on that string.

Exercise 1: Major Triads on G/B/E

We are going to find and play all 12 Major triads on the top three strings, in every inversion, by moving through the cycle of fourths.

You'll likely find this exercise quite difficult at first. Don't even attempt it until you are confident that you KNOW the notes on the fretboard. It's sufficiently difficult that you'll probably want to avoid performing this exercise with a metronome for quite a while. Wait until you are quite confident you can find all the triads quickly before even attempting to use a metronome.

First find and play the B Major root position triad with the root at fret 4 on the G string. Then play the 1st inversion B Major with the root at fret 7, then 2nd inversion with the root at fret 12. Continue up the neck as high as you can reach comfortably, e.g. the root position triad at frets 16-18 if you can reach.

Next find all the close-voiced E Major triads on the top three strings. Then all the A Major triads.

Continue through the entire cycle of fourths: B E A D G C F B♭ E♭ A♭ D♭ G♭, and then back to B where the cycle repeats.

As you progress through the cycle of fourths, always start with the lowest triad you can find on the top three strings (the inversion closest to the nut). Try not to always start with the same inversion.

Trying to find the lowest triad may seem difficult at first. Just remember the open strings are G, B, and E. Whatever note you're looking for is going to be within a few frets of one of those notes. Sometimes the inversion you first consider needs (imaginary) notes below the open strings. Since you can't play imaginary notes, visualize the next inversion higher than the one you imagined first, and play that.

You can be very confident that you know the top three strings of the fretboard well if you can perform this exercise with a metronome, playing whole notes at, say, 60 BPM.

Next up are minor triads. As we discussed, minor triads are formed by flattening the 3rd:

Exercise 2: Minor Triads on G/B/E

Repeat Exercise 1, but this time use minor triads instead of Major triads.

Diminished and augmented triads are used far less frequently than Major/minor, but they are still very much worth learning.

The diminished triad is part of diatonic harmony. A diminished triad is formed by stacking thirds beginning on the 7th scale degree. When harmonizing the C Major scale, the seventh scale degree is the note B. The notes B, D, and F (stacked thirds from the scale) form the B diminished triad.

Diminished triads are also useful when playing over dominant seventh chords. The chord G7, for example comprises the notes G, B, D, and F. Thus a G7 chord “contains” two triads: GBD (G Major triad) and BDF (B dim triad). As weird as it sounds, it’s completely legit to think of a B diminished triad as a G7 without the root note! If someone else in the band plays the G note or G Major chord, playing B dim triads will create the dominant 7th sound of a G7.

Exercise 3: Diminished Triads on G/B/E

Repeat Exercise 1, but this time use diminished triads instead of Major triads.

Next up are the oddest of all: augmented triads.

Because augmented triads are formed of two stacked M3 intervals, they are completely symmetric. C+ (or “Caug”) for example comprises the notes C, E, and G♯. The interval between any pair of notes (C/E, E/G♯, or G♯/C) is a major third. This creates a surprising result when you look at it on the fretboard:

All the shapes are the same! Isn’t that weird?

This means that although there are technically only four different augmented triads, not twelve. The left-most shape above with the notes C/E/G♯ can be considered one of three different augmented triads:

-

C+ (root inversion)

-

E+ (2nd inversion)

-

G♯+ (1st inversion)

Which one you call it depends on the current context. There is only one shape to learn on each set of three strings. If you move the shape up or down four frets, you are forming a different inversion of the same chord (skipping over the three different chords on the intervening frets).

Exercise 4: Augmented Triads on G/B/E

Repeat Exercise 1, but this time use augmented triads instead of Major triads. Because the shape never changes, only the position, you should find this one relatively easy.

Next, let’s look at the triad shapes on different strings