What better topic for the first post on my new guitar site?

Almost everyone who’s ever picked up a guitar knows good ole “box 1” of the Am pentatonic scale. What could possibly be wrong with that as a starting point?

Guitar teachers have long believed that this is a terrific “scale” to teach beginning students. Like countless others, it was the very first “scale” I “learned” as well. (As we’ll see, just memorizing a shape is a long, long way from truly learning a scale.)

Instructors say things like:

The shape is dirt simple and easy to memorize.

It’s incredibly versatile — it sounds great over almost any song: rock, blues, whatever.

A pentatonic scale is just five notes, it’s easy!

Just move the shape to the appropriate fret for whatever key you’re in and wail away! You’ll sound just like an accomplished old bluesman making music on his porch.

Students excitedly start to believe that this guitar stuff might not be quite as difficult as they initially thought.

Sadly, they are wrong. Learning to solo is much, much more difficult for most people than they even imagined. If you’re anything like myself, you quickly discovered that your “solos” using the “box 1” shape didn’t, uh, sound quite as nice as those of your instructor or guitar heroes.

The instructor’s first statement was absolutely true: the shape is easy to memorize. Therein lies the problem. The sexy siren-song of simple-to-remember shapes caused me and countless others literal years of confusion.

After all, we first learned chords as shapes up in open position (usually starting with “G”, “C”, and “D”). For many guitarists, a C chord is that shape up in open position — they never learn any other way to play it, and it’s the only thing they think of when they hear “C Major chord”.

Why not learn scales as shapes in the same way? Millions of people have learned to strum along to songs after learning chords as a few fixed shapes. Can’t we learn scales in the same way?

Unfortunately, music is comprised of rhythm and notes, not shapes.

Learning shapes isn’t wrong, but many guitarists make the mistake of only thinking in terms of shapes (they never learn the notes that make up the shape). It’s impossible to learn to play the instrument without memorizing some shapes.

But a C chord is absolutely not that three finger shape you make up at the top of the neck. That’s merely one way to play the chord, one shape — there are literally dozens of ways to form a C all over the neck. And that shape isn’t even particularly simple or efficient, you really only need to play three strings to play a full blown C chord! (Ever notice how pros always seem to make incredible sounds using just two or three fingers?)

The same thing holds true for scales: scales aren’t shapes in exactly the same way that chords aren’t shapes.

I believe the single best thing a guitarist can do to improve is to stop thinking about shapes and start thinking about notes and rhythm. Shapes are unavoidable and quite useful as a memory aid, but they aren’t the point. Don’t feel bad about using them to organize your thoughts and speed your recollection, but always remember that they are just a tool. It’s the notes that matter.

While the “box 1” shape is easy to memorize, the instructor’s second statement was a bit of a stretch.. A minor pentatonic scale just played up and down in order over a chord progression will sound pretty lame pretty quickly. Just randomly hitting notes within the shape will also sound equally amateurish and, well, random. Sometimes a given note within the scale sounds great, sometimes not so much. It all depends on when you play the note (over which chord and where within the beat) as well as how you articulate it (vibrato, slides, bends, harmonics, muting, dynamics, hammer-ons, and pull-offs all have a profound effect).

Your instructor and guitar heroes know which notes to emphasize (when and how). It’s eventually possible to figure out how to do the same just using your ear, pig-headed persistence, and hours and hours and hours and hours of practice. I’m hoping to short circuit the process at least a bit, though.

And what does the instructor mean by “just five notes”? That box 1 shape has twelve notes within it. Obviously, some of the five pentatonic notes must be repeated within the shape, but which ones and where?

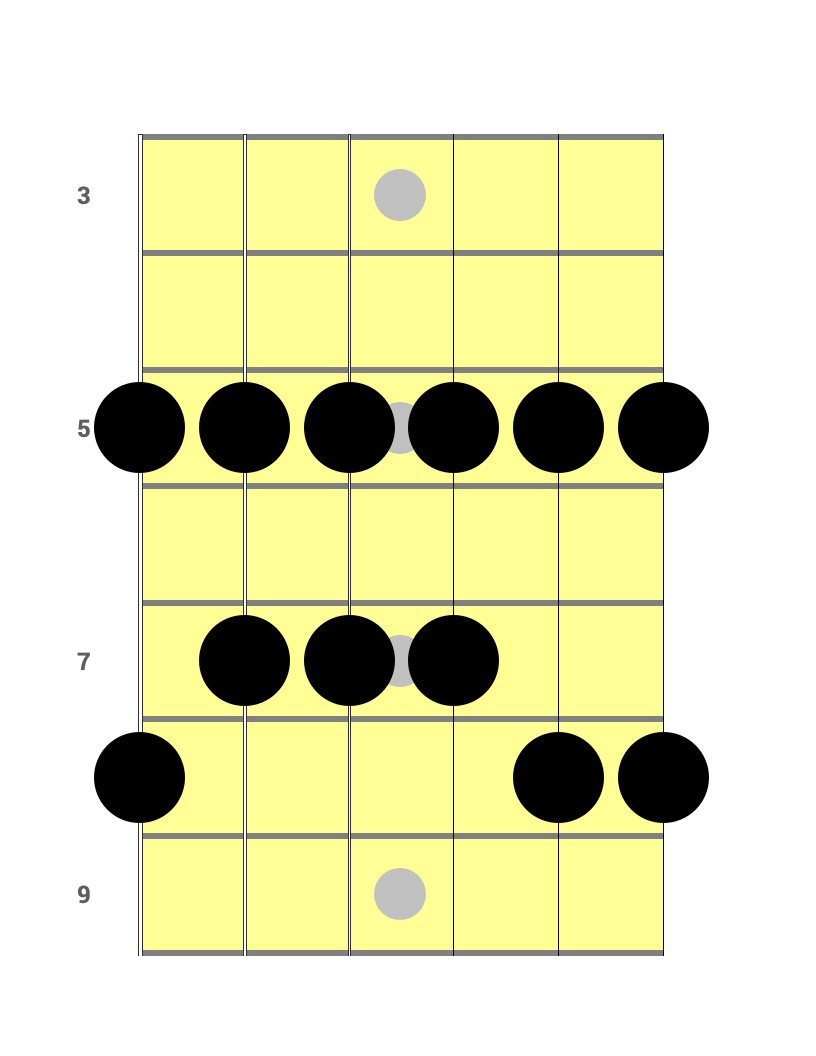

Here is a far more informative view of that same shape for the key of Am. Even with all the extra information contained in this diagram, it still leaves out a bunch of other useful tidbits. Don’t panic, though, it’s still the same shape, just with the neck turned on its side.

The first thing to notice is that there are indeed only five unique notes within the shape, labeled R, b3, p4, p5, and b7 (just repeated two or three times each). The “root” or starting note of a scale is particularly important, so it’s highlighted in red in the diagram.

My primary beef with teaching this “box 1” shape first to new students is the fact that it contains each scale note in multiple locations. Simply remembering which ones are roots and where they lie can be surprisingly difficult when you’re trying to play in time, much less keeping track of the other four notes. Backing tracks, commercial music, and band members insist on continually changing chords with dishearteningly fast rhythms. They aren’t going to wait for you to find the right notes.

In the next post I’ll introduce a far simpler shape that only contains one of each note. It’s a whole lot easier to remember in time where the root is when there is only one root within the shape.

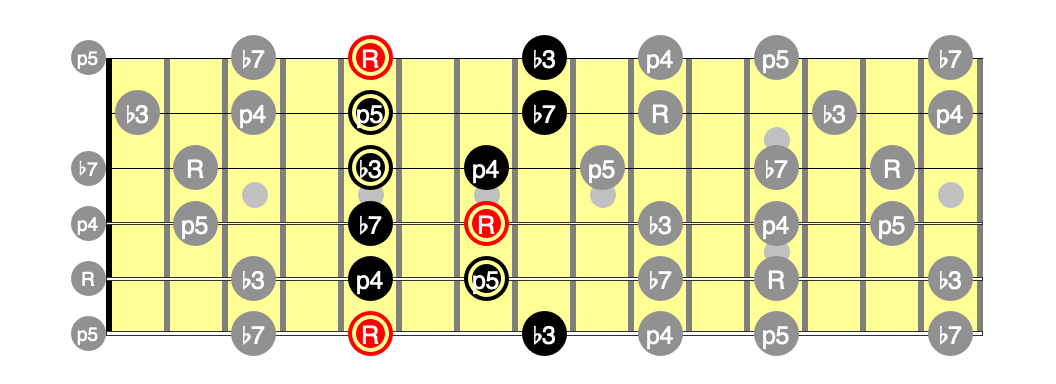

The next thing to realize is that the “box 1” or “root position” shape is just one of many dozens of potential groupings of the five notes in the pentatonic scale. You can make several other shapes using all those greyed out notes in the diagrams.

Most guitars have six strings, and most guitarists have only five fingers (well, four, since the thumb is mostly useless for fretting) so it’s probably not surprising that guitarists tend to organize scales into six-string shapes that span just four or five frets.

But shapes aren’t scales.

The Am pentatonic scale comprises the five notes A, C, D, E, and G. Full stop. Those notes can be repeated as many times as you want, in the same or different octaves.

The Am pentatonic scale is all of the notes in that last diagram, including all the greyed out ones.

Whether you call it box 1, root position, or fifth position, that grouping of notes in the previous diagram is just a shape not a scale.

The most common way of memorizing the Am pentatonic scale is to break it up into five different 4- or 5-fret groupings of notes. Box 1 (AKA “root position” or “E shape”) is just the first one of those groupings that people study. The goal, however, is to be able to freely move between any of the different shapes to play any of the note in the above diagram, greyed out or not.

If you know barre chords, you may recognize why some of the notes in that last diagram are circled. The chord shape is highlighted to make the shape easier to remember. An Am barre chord is formed at the fifth fret using the circled notes.

In the next post we’ll go into much more detail about how to apply this information and actually start making some music.