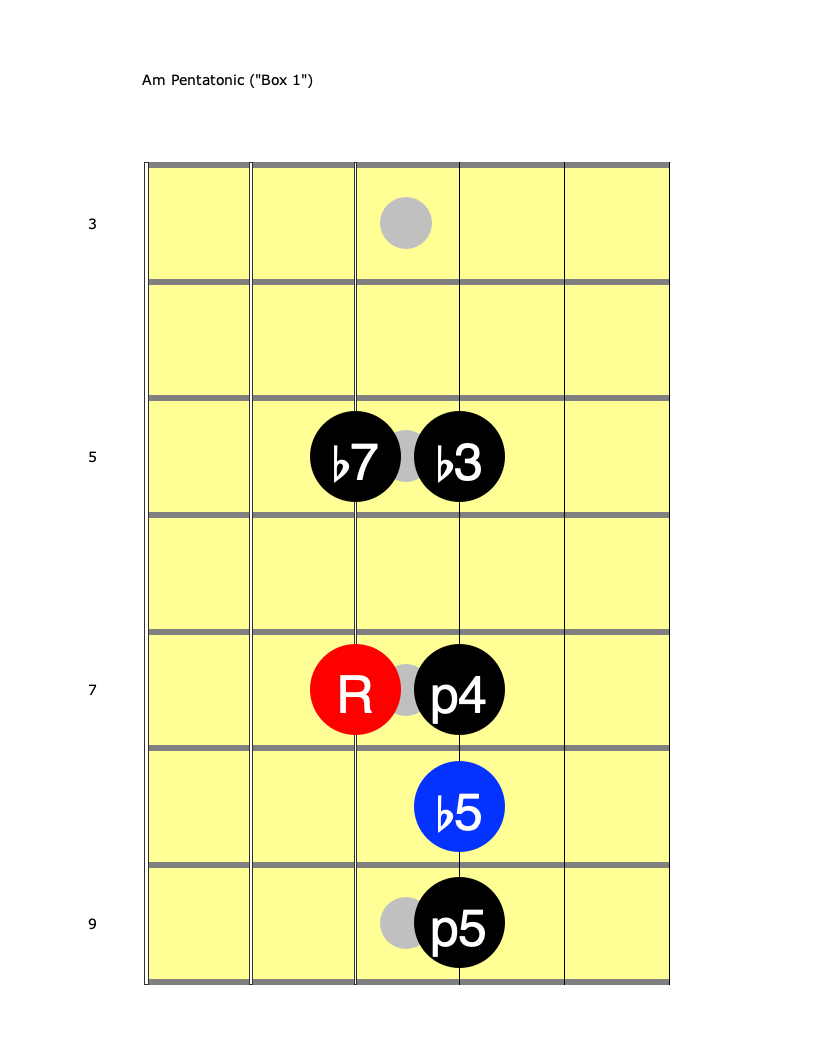

Let’s wrap up our look at the minor pentatonic scale by looking at some of the “between” notes, especially the b5 note that lies between the p4 and p5 (known as the “blue” note).

This is part 4 of my series about learning the Am pentatonic scale. Each post builds off of the previous, so you may want to read these first:

- Part 1. What’s wrong with Am Pentatonic?

- Part 2. The Frying Pan

- Part 3. More Pans

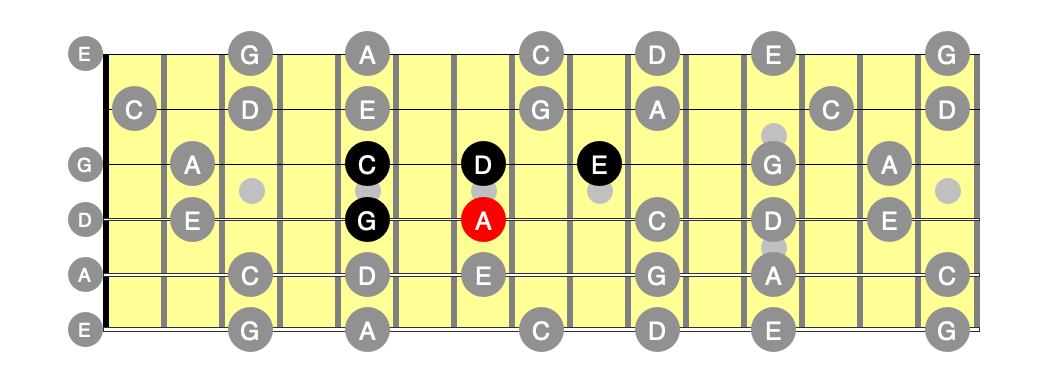

First, let’s review. Here’s the Am Pentatonic Scale everywhere on the neck, with the frying pan shape highlighted in the middle.

Notice first that there are a few more frying pan shapes buried within the diagram that we haven’t covered. There’s one starting with the G at the 10th fret of the 5th string. This shape connects diagonally to other frying pans in the same way, starting with the adjacent shape start with G on the 12th fret of the 3rd string. This one is “squished” a bit because of how the guitar is tuned: the notes on the second string shift a fret higher, but it’s still the same shape. It in turn connects to the G and A on the 15 and 17th fret of the first string (if your guitar has that many frets) but then you run out of strings and can’t complete the shape.

Lastly, open strings are also fair game. There’s another complete (but squished) frying pan starting with the open G on the 3rd string. This again connects to the first two notes of another frying pan starting with the G on the 3rd fret of the 1st string.

All of these are useful locations for soloing. Just remember that whenever you put your third finger down on an A anywhere on the fretboard, there is a frying pan right under your fingers that connects diagonally to other frying pan shapes above and below.

Put on an Am backing track and slowly play through each note of the original minor pentatonic scale, using all of these frying pan shapes, but saying the note names and/or scale degree (root, b3, etc.) out loud as you play it. Ensure you are completely confident about which note you are playing each time.

Be sure to do this in multiple octaves around the neck. Repeat each note multiple times in a row. Really hang on to each note to get the sound/feel/taste of it in your mind. Try moving to each note from different notes in the scale to see how it sounds as the destination of a phrase.

Here’s how they sound to me over Am:

Root A

This is by far the most consonant sound. It feels like home. It sounds good, sweet, complete. Pure sugar.

b3 C

C sounds like longing, or sadness. It fits over any Am chord (Am, Am7, Am9, Am13) and sounds like it belongs, but it really emphasizes that minor/sad/savory quality. Like a sweet onion.

4 D

D sounds slightly uncomfortable over an Am. The longer you hang on it the more uncomfortable it becomes. It doesn’t sound immediately wrong, but it feels like it wants to go somewhere else. Maybe like thyme: really great in moderation.

5 E

E sounds nearly as resonant as A. Not quite home, but at least the front porch. Especially so when coming from an A. Maybe brown sugar or molasses.

b7 G

G Am sounds “cool” or “jazzy” to me. If the backing track is playing Am7 or another minor extension, the G note is part of the chord, so it will definitely sounds like it fits. If the band is just playing Am triads (just plain old Am not seventh chords or extensions) then it still sounds cool, and gives it that jazzy minor seventh vibe. Technically, you are playing an Am7 when you play the G note over an Am triad! (Am7 comprises the notes A, C, E, and G). It’s like cinnamon – goes great with almost anything.

So in summary, the p4 (D) is the only note you need to be careful with over Am, everything else is just compatible spices. They all sound a little different, but they all work. You probably don’t want to hang onto a D too long. Unless you do! Sometimes a song wants that extra tension.

These feeling/taste analogies only go so far. One big difference with music is that these sounds/feelings/tastes change every time the underlying chord changes. A song in the key of Am might contain the chords Am7, Dm7, Em7 and E7. All five notes in the pentatonic scale will work over any of these chords since they are all in the key of Am, but the sound/feeling/taste changes as the underlying chord change. That D note, for example, will sound sweet as sugar when the chord changes to Dm, for example.

Now let’s examine the first of the “between” notes, the b5 between the p4 and p5 (the note Eb in the key of Am). This note is special enough that it gets its own name: the blue note. In fact, it’s so special that the resulting six-note scale with the added b5 becomes “the blues scale” (or, more specifically, the minor blues scale).

Try playing just the Eb note over an Am backing track. Same drill, really hang on to it with multiple repeats. Try moving to it from other notes within the scale, just ending up in the middle of the handle on that b5.

Yuck!

Doesn’t sound too sweet does it! It probably sounds pretty awful.

I like to think of it like well-ripened, stinky, limburger cheese. A little goes a long, long way, but in moderation (and accompanied with some rye bread and good dark beer) it can be amazing.

Instead of making the blue note a destination that you end up on and hang out on for a while, try making it a note you move from. That is, move it earlier into a phrase, perhaps off the beat, and end up on one of the pentatonic notes nearby. Use it as a passing note between other notes.

In particular, try playing the blue note over an Am backing track, then hammering onto the p5. Ahhhh! Doesn’t that sound great? It’s the sound of tension, followed by release. Try sliding down from b5 to p4. Try sliding between all three notes, p4, b5, p5 — just be sure to end up anywhere but the b5! That is one of the quintessential sounds of the blues.

Be sure to fool around with bends, too. Try bending the p4 up to p5, then releasing slowly and picking the b5 on your way to p4.

Try using it between other notes, too, not just the p4 and p5.

Okay, one final sound to, uh, look at before we move off of the pentatonic scale.

The note between the b3 and p4 is the major 3rd. In the key of Am, it’s the note C#. In general, C# will sound horrible over any Am chord because it clashes with the minor/b3 note (C).

But the other defining sound of the blues (minor blues or major blues) is the interplay between major in minor. While a C# usually sounds just plain bad over an Am chord, a C (the minor third) over an A major chord can sound pretty bluesy and cool.

Even over an Am, though, a slight tweak, just a slight bend, of the C# note can sound pretty authentic.

##Try it!

Put on an Am backing track (an entire progression in the key of Am, not just a looped Am chord is fine, just be sure its minor). Practice noodling around with the minor blues scale all over the neck (still just a frying pan shape, but with that b5 in the middle of the handle). This time, though, every time you hit a C at the far edge of the pan, give it a slight tweak or goose. Just enough to bend it a little sharp, but not all the way to C#. Done right, it should make your phrases sound authentically bluesy.

Have fun with this!

Be sure to practice the blues scale using the same patterns we’ve already covered (but now with a six-note scale): strings of three, strings of four, every other note.