Hopefully our exploration into minor pentatonic scales wasn’t too exhaustive. We are going to speed up a bit as we delve into the major pentatonic scale. This isn’t because it’s any less important (far from it) but rather because all of the study methods we’ve already covered are equally applicable. It’s basically just rinse and repeat, but with a different set of five (or six) notes in a slightly different shape.

This is part 5 of my series about learning the pentatonic scales.

- Part 1. What’s wrong with Am Pentatonic?

- Part 2. The Frying Pan

- Part 3. More Pans

- Part 4. The Blue Note

Each post builds off of the previous, so you may want to read the prior lessons first.

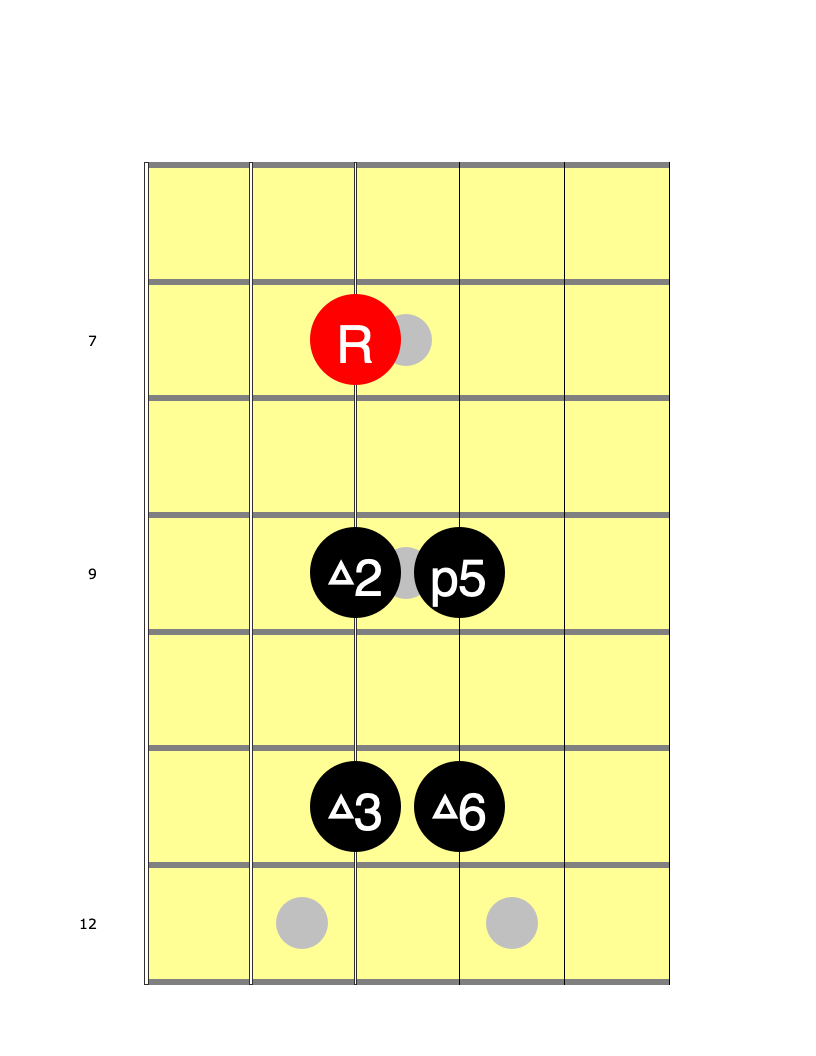

Let’s continue, however, with something new. Here’s the five-note major pentatonic shape we are going to study:

In this case, this is A major pentatonic because it shows the root on the 7th fret of the D string (which is the note A).

With minor pentatonic, we position our ring finger over the root note to be in position to play the scale. For major pentatonic, we just move our hand two frets higher and place our index finger on the root note.

I’m going to repeat that because it’s important (and makes things way simpler to actually play): Place your ring finger over the root to play minor pentatonic patterns. Shift up two frets and place your index finger over the root to play major pentatonic scales.

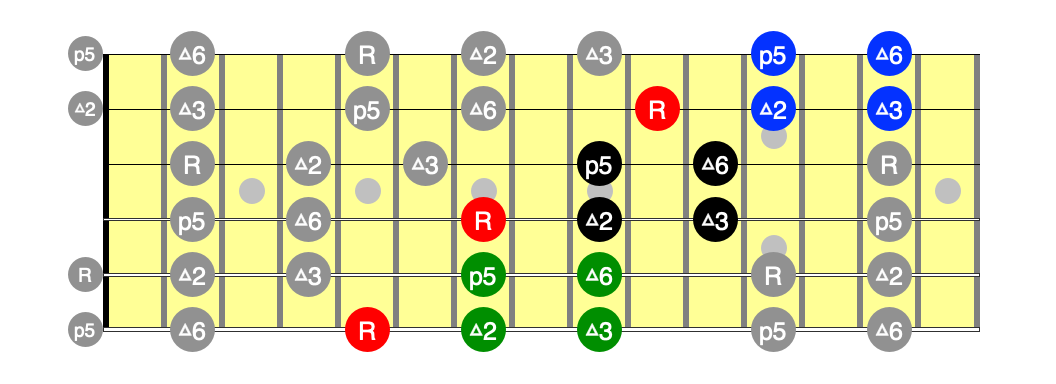

A major pentatonic comprises the notes Root, Major 2nd (M2), Major 3rd (M3), Perfect 5th (P5), and Major 6 (M6). In the key of A major, these are the notes A, B, C#, E, and F#. The major “frying pans” connect in the same way they did with minor pentatonic:

There are several things you should notice before you start practicing with the major “frying pan”:

-

The “handle” points up the neck (toward the bridge) with minor pentatonic, and down the neck (toward the nut) with major pentatonic. Shapes aren’t music, though, so don’t spend too much effort trying to remember this if it doesn’t help immediately.

-

The first two notes ascending in the minor shape were b7 and root. In the major shape, the first two notes are root and M2 (thus you should move your hand up two frets to play major).

-

In minor pentatonic, the root was at the heel of the pan. With major, it’s at the end of the handle. (Again, shapes aren’t music — feel free to ignore this if it isn’t helpful or takes any effort to remember).

-

The octave shapes are always the same, regardless of the scale. Each new root is found two frets and two strings higher than the first (adding a fret whenever crossing the G/B string boundary).

-

In fact, all interval shapes are always the same: the p5 note is always two frets and one string higher than a root note, or on the same fret but one string lower. (As always, account for the tuning anomaly at the G/B boundary by adding or subtracting a fret depending on which way you’re moving).

Again, try to think about notes as much as possible, and not about shapes. Only use shapes to help you remember. Point 2 is far more important than point 1.

Regardless, we need to practice the major pentatonic scale in exactly the same way we practiced the minor pentatonic scale.

Try it!

-

Put on a major backing track in A. At first, just loop a single chord in one or more octaves (A or A7 would be a good choice) but eventually you can use any chord progression in the key of A major (just be sure it doesn’t modulate to a different key). Learn the sound of each of the major pentatonic notes, slowly play each note repeatedly over the chord, and note how it sounds to you. Try moving from different notes to the target note. Play in multiple octaves all over the neck. Again, iReal Pro is the ideal tool for creating whatever backing track you want.

-

Experiment with slides, bends, hammer-ons, pull-offs, vibrato. Try various rhythms. Just be sure you know what note you’re playing at any instant (both it’s name and function/scale-degree). Ideally, try to anticipate how a note will sound before you play it (I still struggle with this).

-

Try to play lines rather than just random notes. Think about where you are going. When you find a phrase that you like, repeat it then expand on it.

-

Next practice fixed scale pattern sequences over the connected shapes. First just linearly ascend and descend the connected scale shapes. Then play sequences of three, then sequences of four, and finally every other note (“thirds”).

-

Next it’s time to explore the same two “extra” notes, the b3 and the b5. Over major chords, you’ll probably find that the b5 just sounds wrong. You’ll probably only ever want to use the b5 as a very brief approach note to get to the p5 or M6. The b3 over major chords is interesting, though. As we discussed, it kinda works. Over major chords, the b3 becomes the “blue” note, just like the b5 is the blue note over minor chords. You probably don’t want to hang out on it too long, but that minor over major sound is definitely a big part of the blues. Spend some time making lines using the b3 over major chords, it’s worth the effort. In particular, try “tweaking” the M2 just a little sharp with a bend. Bending the M2 a little sharp over a major chord feels every bit as “bluesy” and sweet as tweaking the p4 over a minor chord (or at least it does to me).

After all this ridiculously thorough exploration into just two scales (plus “extras”) you’re about to get an enormous payoff:

You now know everything necessary to create amazing, soulful, expressive solos over almost any blues, pop, R&B, folk, soul, or rock song. Seriously, these two scales are the keys to the kingdom. An uncountable number of amazing guitarists use almost nothing else. Once you’ve truly mastered these, everything else becomes much, much easier to get under your fingers.

To give you a taste, take a moment to appreciate this fantastic video from my current guitar hero, Matt Smith (Matt’s an amazing musician, phenomenal instructor, and, from his bio, an all around terrific human being — I’m currently devouring everything he’s ever published).

Matt’s not the only one I’ve heard suggest to use the major pentatonic scale over the I, the minor over IV, and whichever you like over the V, but that video really hammered it home for me.

Prepare to be Blown Away

Major and Minor sound completely, utterly different. But for every major scale, there is a minor scale that shares precisely the same notes. Seriously, this is mind boggling: the exact same five notes can make you feel happy or sad, taste salty or sweet, or smell perfumed or stanky, just based on which notes you hang out on (or end your phrases with).

To me, this was an absolute epiphany. I hope whoever reads this feels the same way.

On a purely practical level, this drastically reduces the number of shapes and movements your fingers need to make. Major and minor (and as we’ll see, other “modes”) follow the same shapes on the fretboard. Train your fingers to find major notes and they also know where to find minor notes (you just need to shift your hand and, uh, flip your brain to re-visualize things).

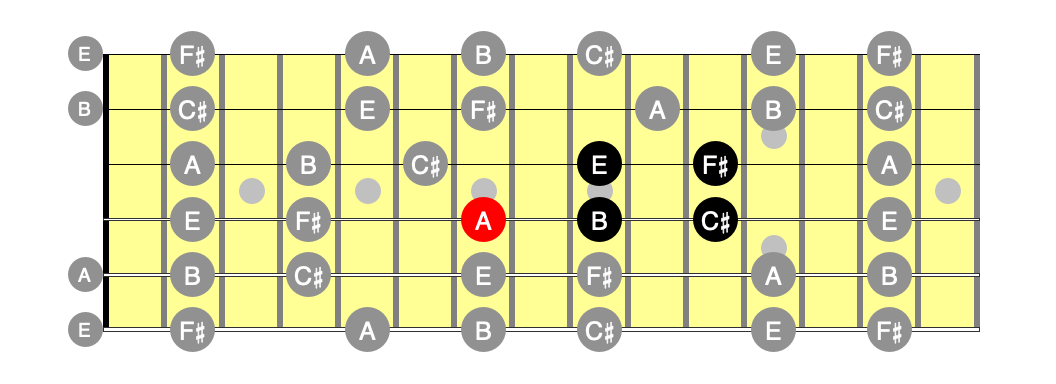

Let’s provide a visual example of what I mean. Here’s the A Major Pentatonic scale everywhere on the fretboard again (this time with note names rather than scale degrees):

To reiterate, just put your index finger down on any A on the fretboard, and you’re in position to play the A Major pentatonic “inverted frying pan” shape.

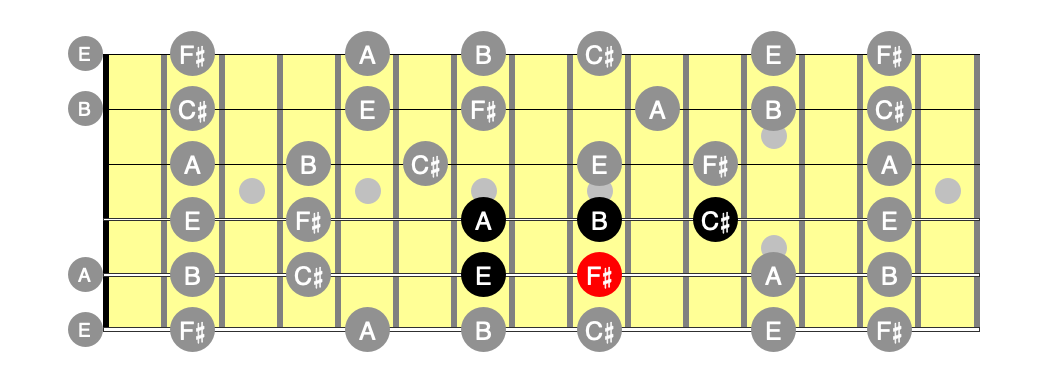

And here’s the F# Minor pentatonic scale everywhere on the fretboard:

Notice anything?

Yup, exactly the same notes. Visualize the frying pan flipping upside down and you convert between major and minor — without changing any notes. Woah!

In other words, you can think about and use this scale (this collection of notes) in two utterly dissimilar ways:

-

You can “think A major” and put your first finger down on an A. Then start playing major sounding licks that emphasize (end on) the A, C# and E notes (the notes in an A major triad).

-

You can “think F# minor” and put your third finger down on an F#. Then start playing playing minor sounding licks that emphasize the F#, A, and C# notes (the notes in an F# minor triad).

In other words, the “relative minor” of A is F#. A Major and F# Minor are different scales but they share exactly the same notes.

Every major key has a relative minor (precisely a major sixth interval up from the root). A major sixth interval is nine half steps (nine frets) above the root (which is easier to find as three frets below the root).

You can use fretboard shapes as a tool to find the relative minor of any major key: Look at the relationship between A and F# in the previous two diagrams. The major sixth of any note can be found one string lower and two frets higher. It can also be found one string and four frets higher.

[This tool is most useful if you’ve already learned the names of all the notes on the fretboard. I strongly, strongly recommend that you put in the time to learn them if you haven’t already.]

This concept of the same collection of notes having very different sounds depending on which notes you emphasize is known as modality.

In this post, we’ve been looking at a five-note scale comprised of A, B, C#, E, and F#.

If we emphasize A (making it feel like “home”) we call the scale major.

If instead we make F# feel like home (by ending our phrases and “resolving” to F#) we call it minor.

To this point, we’ve only been discussing 5-note “pentatonic” scales. It turns out that literally all of western harmony is derived from a scale with just two more notes. We’re talking centuries of music and millions of songs.

This is for another lesson, but if we add just two more notes (D and G#) to our A Major Pentatonic scale, we get the complete 7-note A major scale. (For completeness, D and G# are also known as p4 and M7 in the key of A.)

Just as emphasizing the F# rather than the A made things sound “minor,” we can emphasize any of the other notes in a scale to create other sounds/feelings/tastes. The A major scale is the seven notes A B, C#, D, E, F#, and G#.

If we play chords and melodies that emphasize and resolve to the note A, we call it “Ionian” (AKA major) mode.

If, however, we use the exact same set of notes to play chords and melodies that emphasize and resolve to F#, we call it “Aeolian” (AKA minor) mode.

Resolving to other notes creates other “modes” (same notes, different feels/tastes) from the same A Major scale:

-

Resolving to A is “Ionian mode” (Major).

-

Resolving to B creates “Dorian mode.”

-

Resolving to C# is “Phrygian.”

-

(Resolving to D is “Lydian,” but it’s not in the major pentatonic scale.)

-

Resolving to E is “Mixolydian.”

-

Resolving to F# is “Aeolian” (AKA minor)

-

(Lastly, resolving to G# is called “Locrian,” but it’s also outside the major pentatonic scale and is rarely used outside of jazz.)

Modes can be confusing, and too many guitarists get hung up on the concept.

Just understand that the same collection of notes can sound very different depending on the chords you play over and which notes are emphasized in a melody. The notes A, B, C#, E, and F# will sound happy and upbeat when resolving to A over the chords A, D, and E, but sad and soulful when resolving to F# over F#m, Bm, and C#m. Same notes (or scales) but different “modes”.