A tritone is an interval of three tones, or three whole steps. It can also be considered a diminished (or flat) fifth (the blue note). Because it splits an octave evenly in half, it has some really cool characteristics and applications (though on its own it will sound pretty discordant and unstable).

The interval between G and D♭ is a tritone, for example, but so is the interval between D♭ and G! Try it on your guitar. Play a G anywhere on the neck, move up six frets (three whole steps) and and you’ll be on a D♭. Instead of moving up six frets, you can also move over to a higher string (a fourth) then up another fret (another half step). Now move up another six whole steps and you’ll find yourself back on another G.

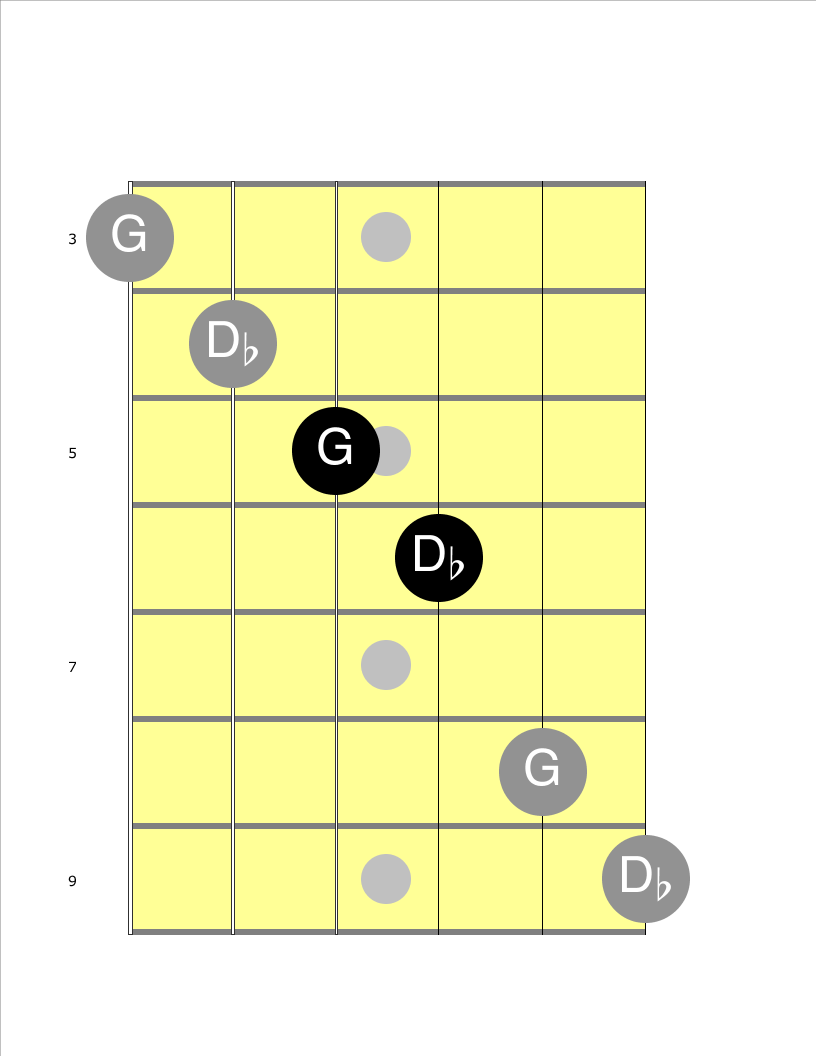

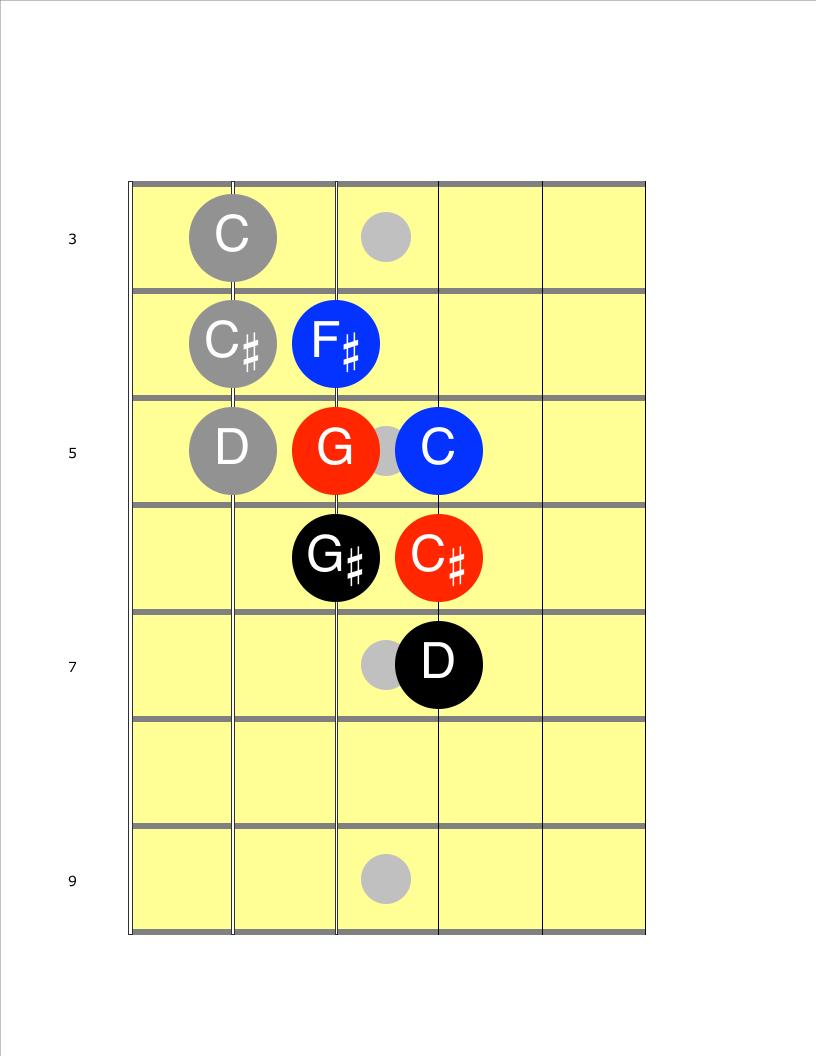

Here are a few ways to play the G-D♭ tritone:

Notice the diagonal shape as you go across the strings, but for now just remember that two-note shape of the dark black notes – over a string and up a fret produces a tritone (everywhere except between the G and B strings as usual). The diagonal pattern as you move across the strings is just a side effect of the octave shapes we’ve covered elsewhere.

This same diagonal pattern repeats every six frets. Starting, for example, on the D♭ at the 11th fret you’ll find another diagonal pattern of these notes but with the notes swapped on each pair of strings.

The fact that the pattern repeats every six frets like this means that there are only six unique tritone pairs (G-D♭ A♭-D, A-E♭ B♭-E, B-F and C-G♭).

It’s really easy to find a play tritones anywhere on the neck.

Application

Great, you think, so what? How do I use this to play actual music?

The short answer is “tritones are the heart of any dominant 7th chord”. The absolute essence of the sound of any chord is the sound of the 3rd and the 7th. With dominant chords, you have a major 3rd and a flat 7th — an interval of a tritone between them.

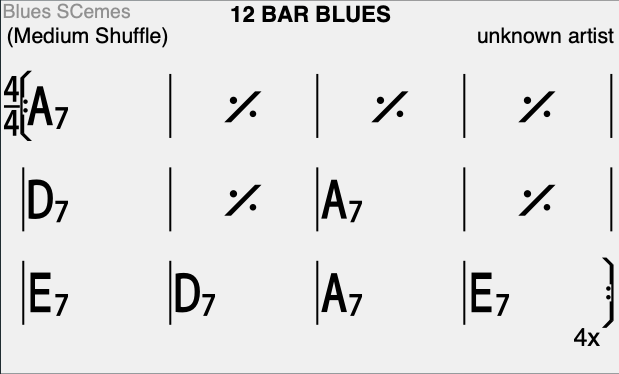

Let’s take a look at a blues in A:

A blues in A uses the chords A7, D7, and E7.

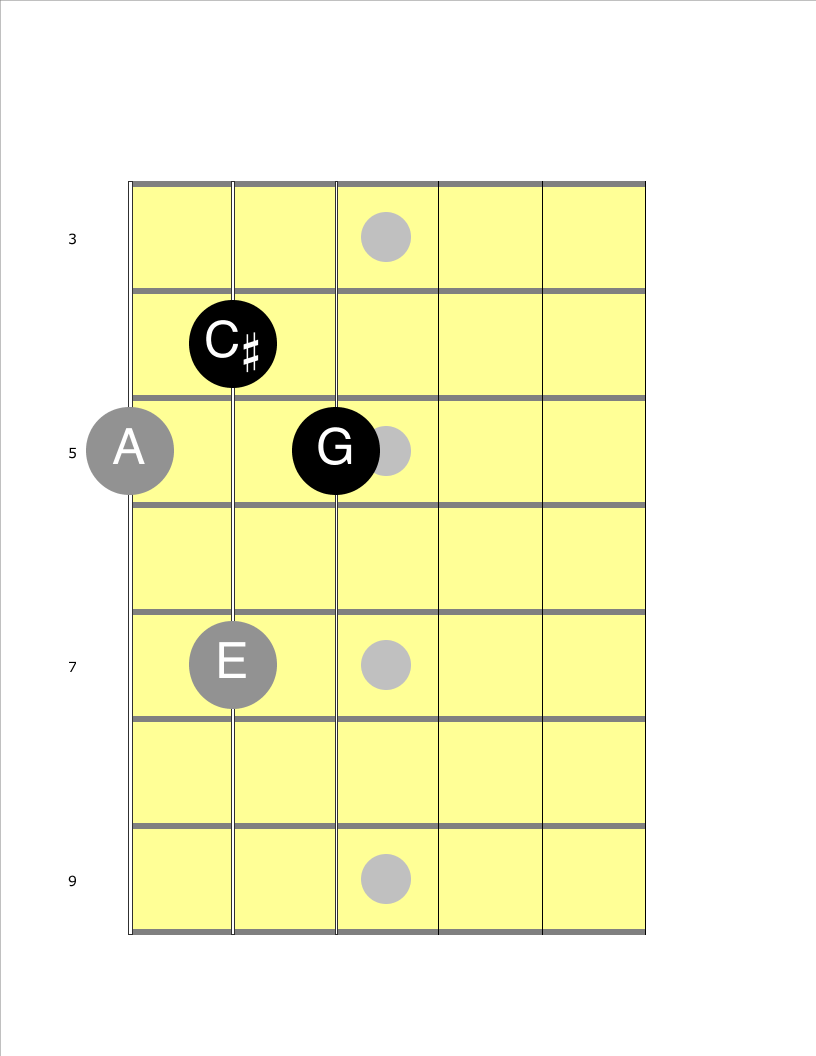

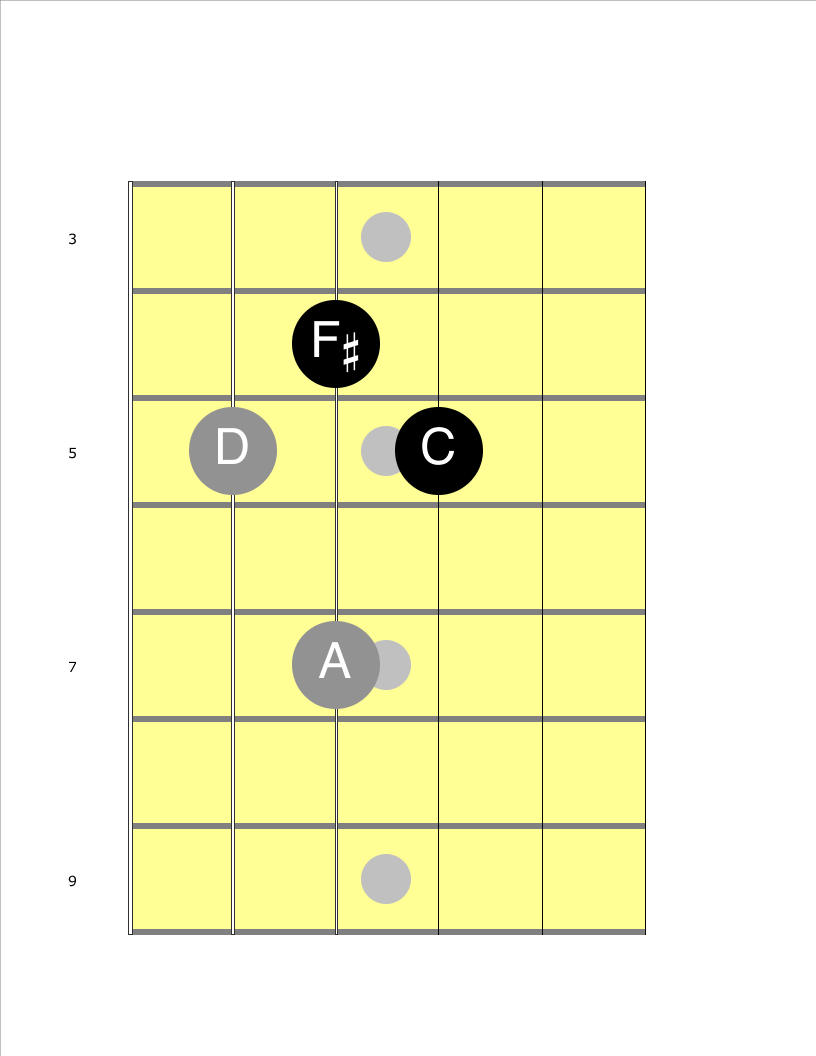

A7 is spelled A (root), C♯ (M3), E (p5), and G (m7). The interval between C♯ (AKA D♭) and G is a tritone. Here it is diagrammed as an arpeggio. Just play the notes in ascending order starting with the A on the sixth string:

Notice that highlighted tritone between the C♯ and the G?

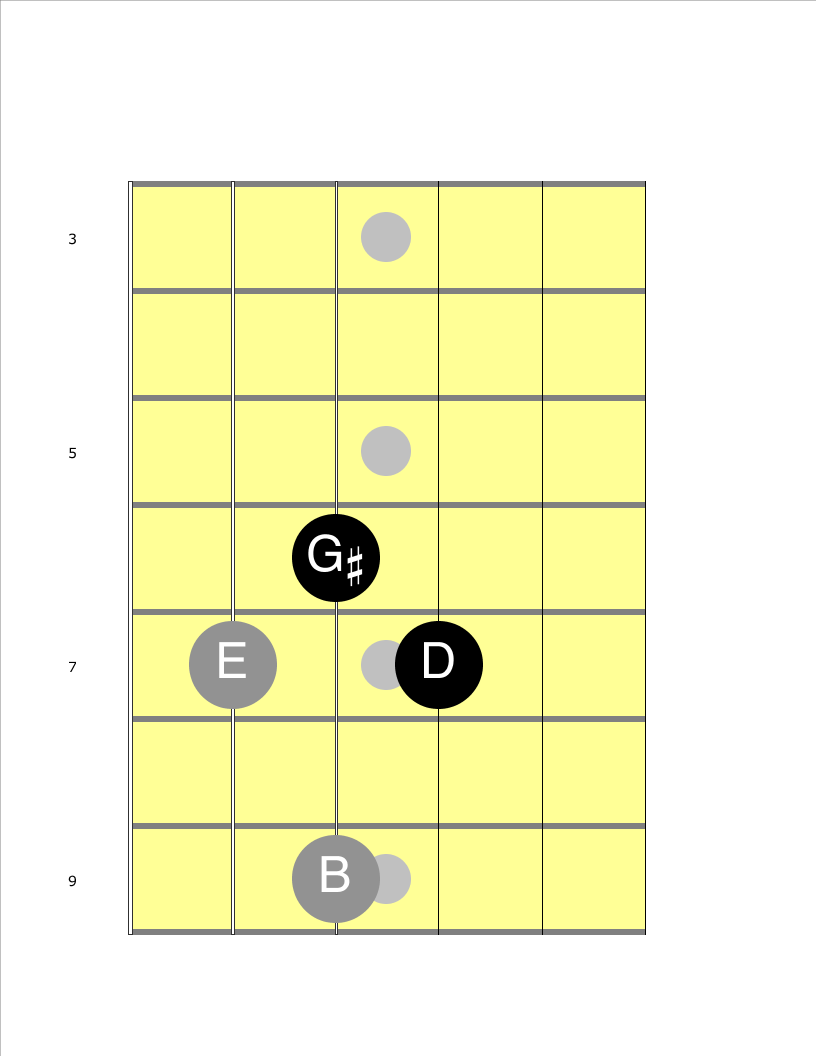

Here’s a D7 arpeggio (the IV chord):

And finally, E7, the V chord:

If you put on a blues in A backing track and play the A7 arpeggio notes over A7, D7 over D7, and E7 over E7 it will sound perfect (if a little dull since there is no “spice” from notes not in the underlying chord).

But that’s twelve different notes to remember (if only a single shape). We can make it even easier.

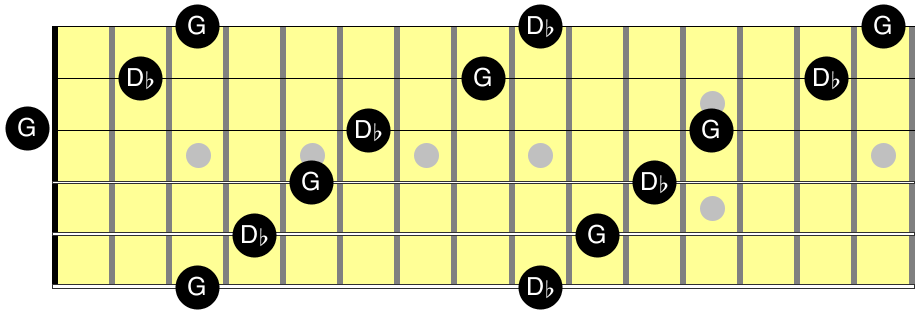

Overlaying the Arpeggios

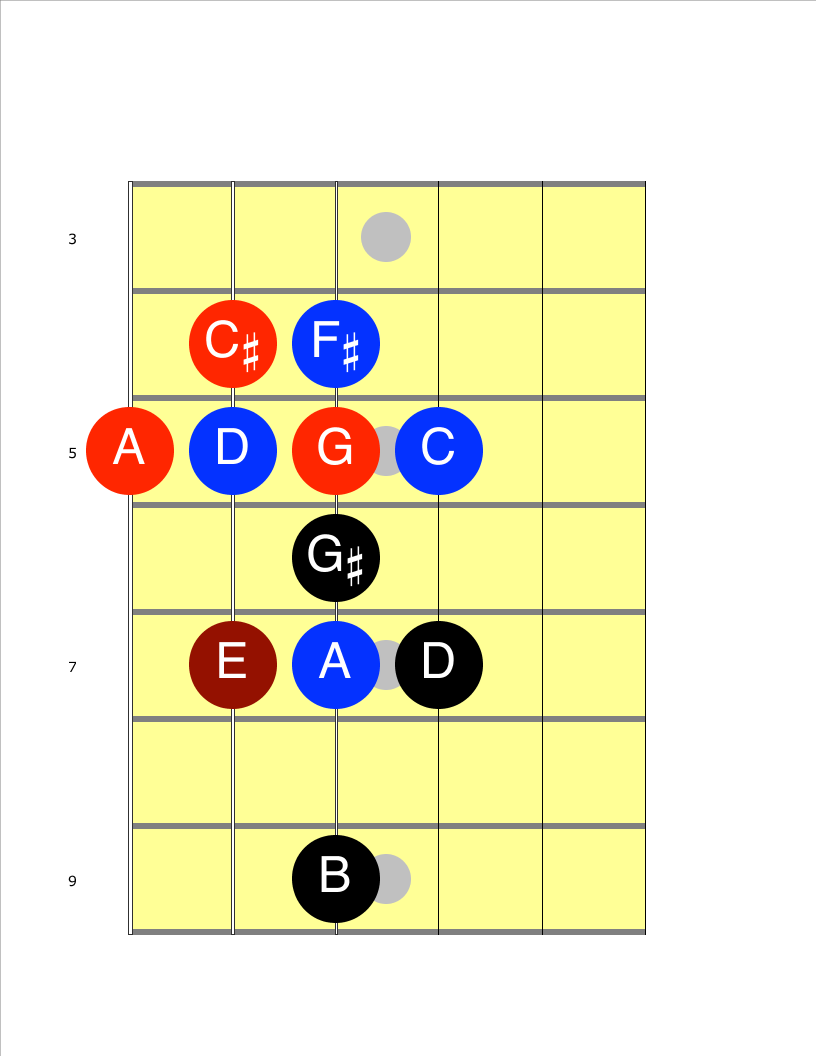

Here’s a diagram of the three arpeggios overlayed on top of one another: red for the I chord, blue for the IV, and black for the V (the note E is shared by both the I chord and the V chord).

That’s a messy cluster of notes, so let’s try to simplify.

I said earlier that the 3rd and the 7th are the most important notes in any chord. They provide the essence of the sound. Perhaps surprisingly, they are even more important than the 5th or even the root notes, especially in a band context.

So lets get rid of all the roots and fifths from each arpeggio:

That’s quite a bit better. Just three tritone shapes. But we can make it even easier yet.

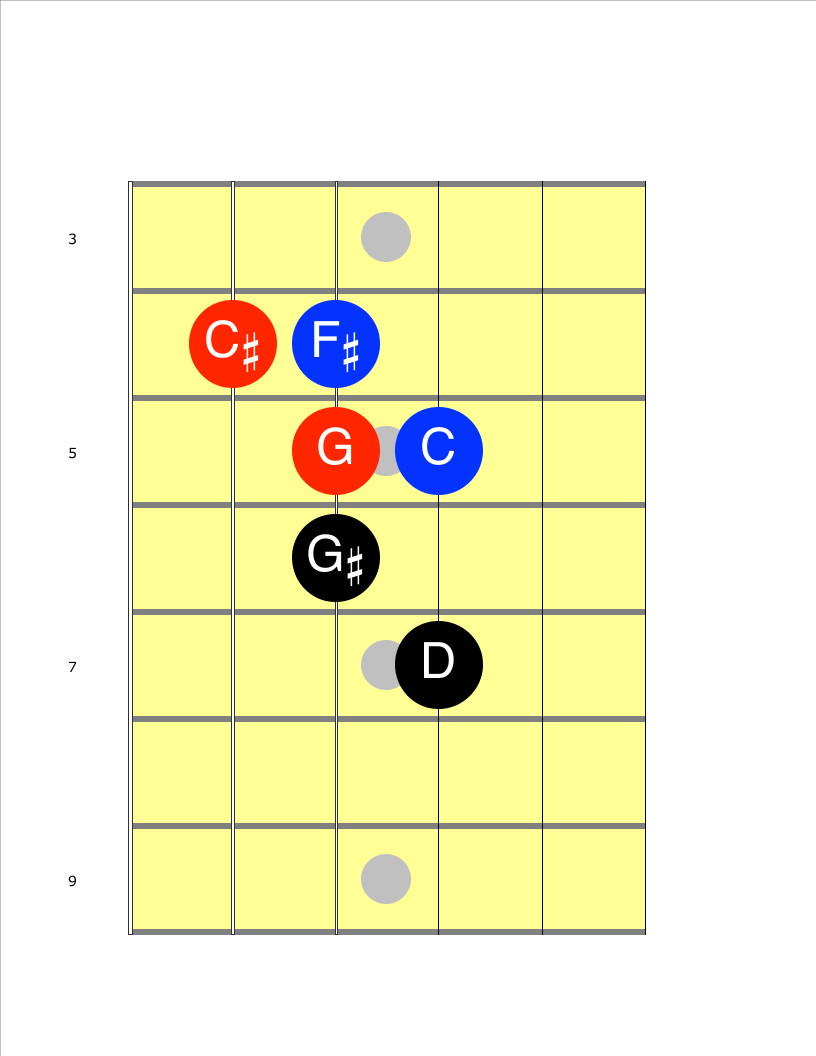

Let’s use octave shapes to move all of the notes onto the same pair of strings:

Woah. This means you can “comp” to an entire 12-bar blues using just two fingers on your left hand! You move your hand lower by one fret when playing the IV chord, and higher by one fret when playing the V!

I’m far from the world’s greatest guitarist, but here’s a video of me using tritones to comp a 12-bar blues. It sounds particularly sweet if you highlight one or both of the tritone notes at the exact moment the chords change:

Soloing and practice

I find it much easier to practice this sort of thing with iReal Pro than anything else I’ve tried. It’s hard to even hear the chord changes when you are a beginner, much less time things to hit the changes on the beat. iReal Pro gives you a fighting chance because it gives you a visual cue of what chord is currently playing, what’s coming up, and where you are within the song.

First set the tempo very slow, and just practice comping along with tritones on one pair of strings. Try hard to change to the next tritone right when the chords change. Vary your rhythm. Try sliding into each tritone occasionally.

Once you are comfortable doing this on one pair of strings, start introducing tritones on different strings. Try to “see” the diagonal set of tritone pairs as a single shape.

Next, start mixing in notes from the pentatonic scale, and/or the full arpeggios. Try to anticipate the sound of each note before you play it (I’m told that singing or humming the notes as you play them helps).

It’s easy to get lost and confuse yourself. One thing that helps me is to visualize where the closest root is for whatever chord I’m on (this is why it’s so important to memorize the fretboard).

If I know where the root is, I can find the ♭7 by moving down two frets, or the 3rd by moving up a string and one fret. If I can find either of those notes, my fingers just make the diagonal tritone shape around it.

To demonstrate the exercise, here’s a rather pitiful video of me trying to solo. I sounded better until I started recording! (Laugh.)

Hopefully, it won’t scare you off the idea entirely. I’m keeping the video for posterity so I can see my improvement.