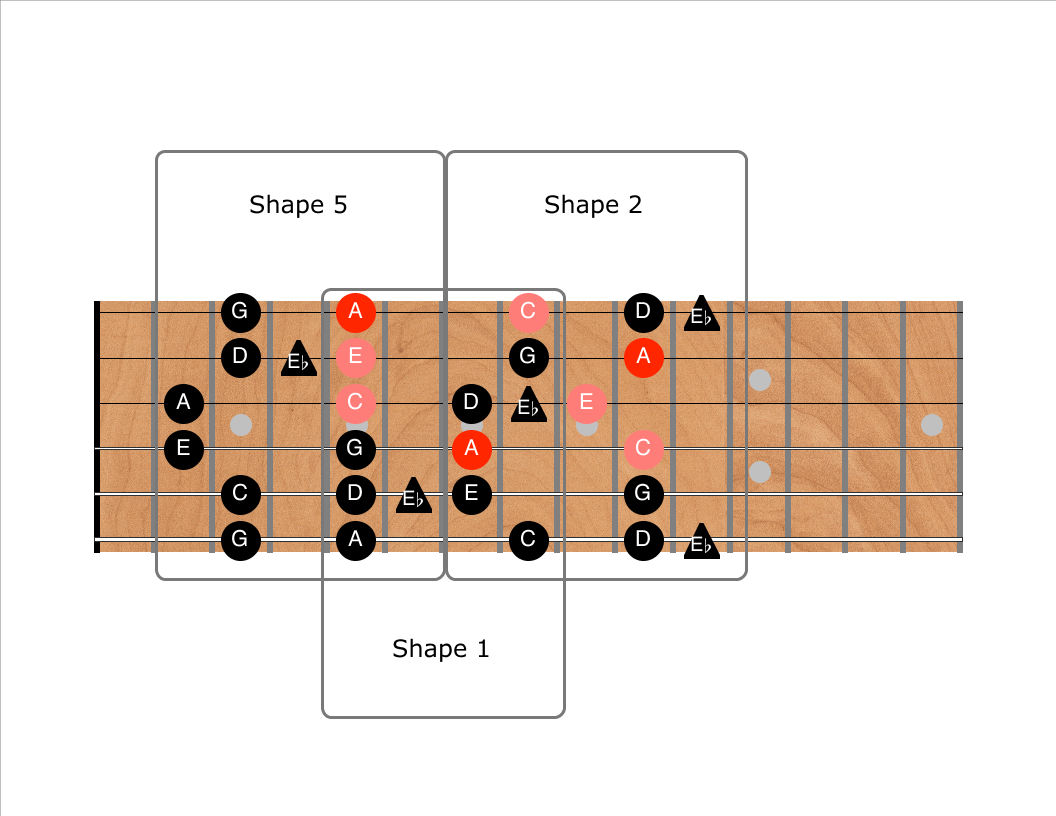

Chords and scales are intimately connected. Consider these three (inter-connected) shapes of the Am pentatonic scale, for example:

The root notes (A) of the scale are shown in red. The remaining notes in the two Am chord shapes on the top four strings are also shown in salmon. (Note that these chord shapes are just triads on the top three strings, with the highest note doubled on the 4th string in a lower octave.) The “blue notes” are shown with a triangle.

This post is about connecting these shapes in your mind. When you play or even think about the Am shape on the top three strings at the 5th fret, your mind should immediately fill in the rest of both Am pentatonic shapes on either side of the chord (shapes 5 and 1). You should practice these shapes until the connection in your mind between the chord shape and the adjacent pentatonic shapes is automatic.

We’ve already learned that the five pentatonic shapes can be either major or minor depending on which notes are emphasized. If you emphasize the A notes in an Am pentatonic shape, it will have a decided “minor” sound. If you emphasize the C notes in the same shape, however, it will start sounding sweeter and more “major”.

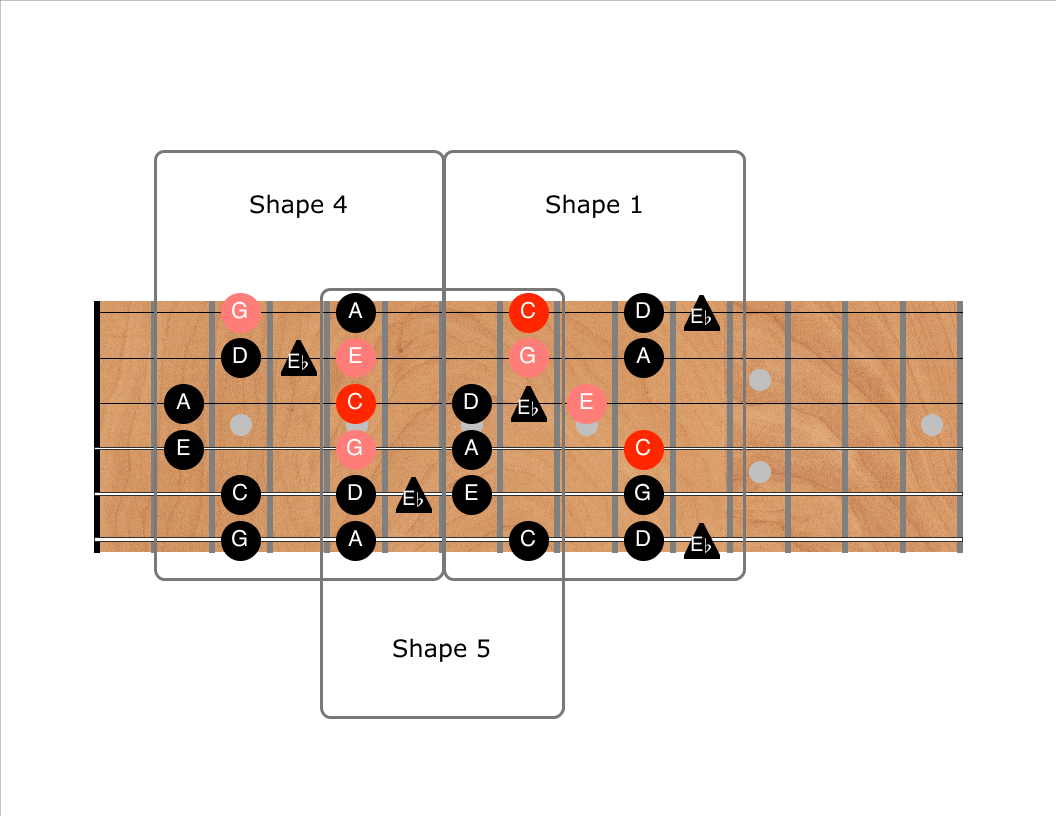

Here are the exact same shapes on the fretboard again, only now we are thinking “C Major” rather than “A minor”:

Do you see how the same pentatonic scale shapes contain both the Am and C (major) chords? If you lower the A notes in each shape a whole step to G, you convert an Am chord (A-C-E) to a C Major chord (C-E-G).

This makes naming the pentatonic shapes difficult. Is it shape 1 of the minor pentatonic scale, or shape 5 of the major pentatonic scale?

As always, shapes and names don’t matter, only sounds matter. The only names that stay constant in music are note names (though “enharmonic” note names like B♭ and A♯ confuse things slightly).

Scale and chord names depend on context. The C Major and A minor scales contain exactly the same notes. Chords are equally confusing, especially since it’s completely legit to leave out the 5 or even the root when playing a chord! If a song calls for a G7 chord, it’s common and reasonable to just play a Bdim triad instead, though you would be thinking “G7 without the root” instead of “B dim” (G7 is spelled G-B-D-F, Bdim is B-D-F). Similarly, C-E-A-C can be thought of as C6 (a major chord) with a doubled root or as Am with the m3 doubled. The same chord can be major or minor depending on context!!

I don’t like talking about shapes or positions for this very reason — it’s just too confusing to have two names for the same thing.

Instead, I like to think of scale patterns “hanging off of” chord shapes, either higher or lower on the neck. Once you learned (truly KNOW) the triad shapes and the five pentatonic shapes, your brain will see how they interconnect and you will never get lost.

No matter where your left hand is currently on the neck, your mind’s eye should “see” the major on minor or chord you’re looking for nearby, and you should also “see” the pentatonic shapes both lower and higher on the neck from this chord.

This takes a LOT of practice, however. I’m working on some drills to embed this into your muscle memory. Stay tuned.