Okay, here’s the third and final chapter of the Killing Floor lesson. This is about the main rhythm guitar riff that Hubert Sumlin plays throughout.

It uses a trick mostly associated with Steve Cropper (think “Soul Man” by Sam and Dave): sliding sixths. (Though I think Killing Floor pre-dates Soul Man by a few years.)

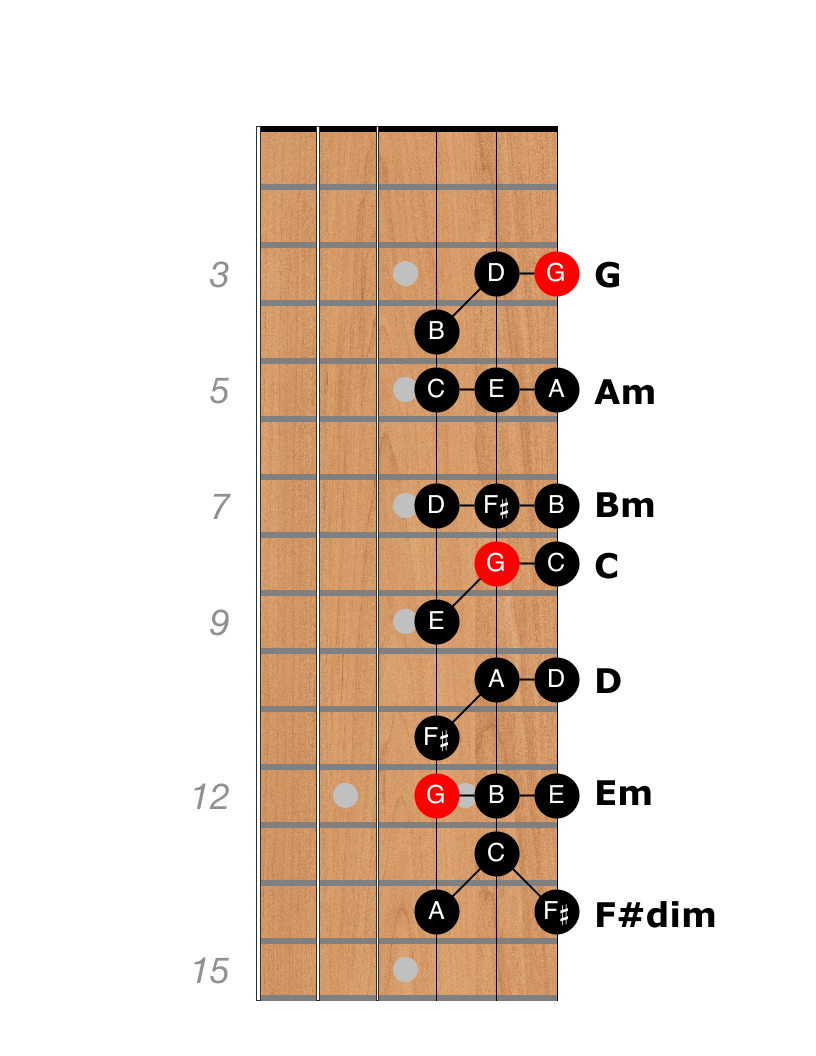

The riff is based on the harmonized scale. For reference, here is the G Major scale harmonized with 1st inversion triads (with the 3rd in the base).

I’ve mentioned before that you can almost always drop the fifth from any chord and it will still be recognizable as the same chord. Basically, the P5 is like monosodium glutamate for the root note: playing the root with the P5 simultaneously still sounds like the root by itself, only meatier!

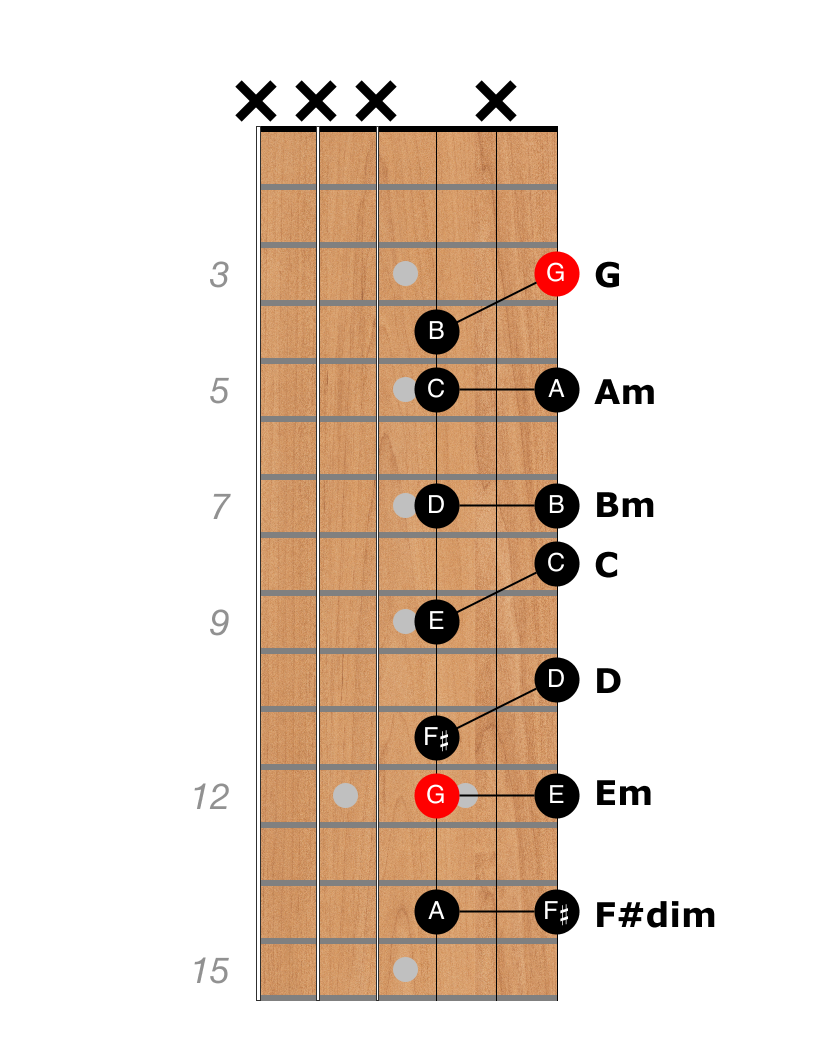

Let’s slim down our sounds by removing the MSG (the P5 notes) from all those triads:

Note that intervals are relative. The name of the interval between any two notes depends on which is the reference note.

In the G Major triad, for example, G is the root and B is the M3. The interval from G (up to) B is called a major third.

If, however, we think of B as the reference note, then the interval from B (up to) G is called a minor sixth. It’s the same two notes, but the name depends on context. When we’re talking about the G Major chord, B is the major third. When we’re talking about the interval from B up to G, it’s called a minor sixth. Confusing, I know.

The convention is to name intervals relative to the lower (bass) note. That is, the lowest note is always the reference. That’s why we call all those shapes in the previous diagrams “sixths”.

If we were talking about the chords we call the bass notes thirds and the higher notes roots. When we are talking about chords (triads) or more specifically scale degrees it doesn’t matter which note is lower, the names are always relative to the root/tonic of the chord.

The technique of sliding between the different two-note groupings is called “sliding sixths”. The Killing Floor riff slides uses just the top three interval shapes (G/Am/Bm) from the previous diagram when playing over the G7.

Because all three interval shapes come from the G Major harmonized scale, they provide a very strong flavor of “G”. That’s what makes them sound so cool over a G7 chord (the notes G, B, E, and A) even though a couple of the shapes include non-chord tones (the C and D notes in the Am and Bm shapes).

The Sixths Riff in Killing Floor

Killing floor is just a standard I7, IV7, V7 blues progression. In the key of G, the chords are:

/ G7 / % / % / % /

/ C7 / % / G7 / % /

/ D7 / C7 / G7 / D7 /

The riff is played in two-bar phrases: two bars of a G riff. Another two bars of G. Then two bars of the riff moved up to C, followed by two bars back down in G.

The turnaround (the last four bars) are played with full chords, not the sixth riff. The turnaround comprises one bar of a full D7 chord, a bar of C7, a G Major (not G7) chord, then the familiar final bar of D9 in straight eighths.

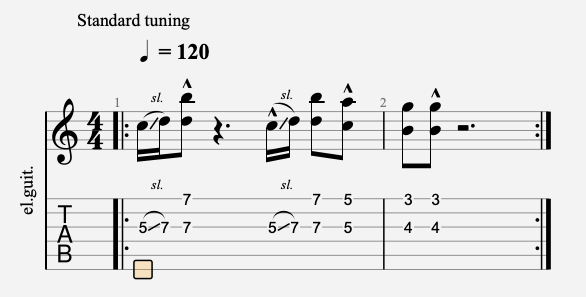

Here’s the two bar G7 riff in tablature (it took me forever to figure it out!):

This is played with a fairly straight feel, not swung at all. The backbeat notes (the “ands”) are strongly emphasized (note the hats over the backbeat notes in the tablature). The tab also shows the initial slides.

The count is “one-e-AND, …, …-AND-uh, four-AND, one-AND, …, …, …". Here is what it is supposed to sound like.

Now that I’ve figured this out, I need to eventually re-record the following (with a better mic!):